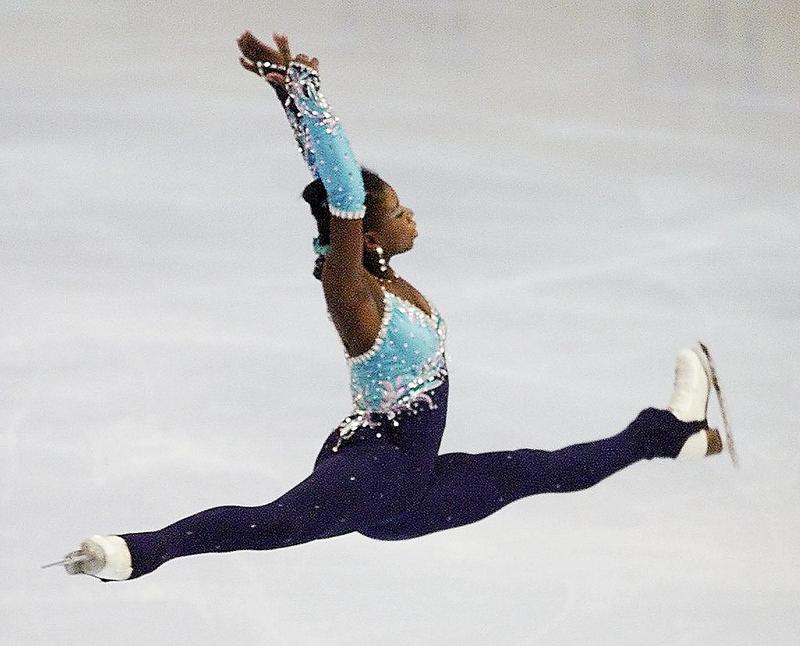

Surya Bonaly broke barriers as a figure skater. Her athletic jumps and spins in each performance struck a chord with audiences, making her an exciting skater to watch. Bonaly skated to the beat of her own drum, the rules couldn’t define her.

Bonaly grew up in Nice, France where her parents encouraged her natural athleticism. She danced, fenced, dove, figure skated, and competed in gymnastics. Although she excelled in each activity, she connected most with figure skating. At only 12 years old, Coach Didier Galihaguet recruited Bonaly to compete with the French National Team.

A Harsh Reality

Coach Galihaguet turned Bonaly into a champion. She won the 1990 World Junior Championships and the European Championships in 1991 and 1992. At the world-class level, however, Bonaly fell short. Figure skating officials and judges expect skaters to dance on ice while incorporating various tricks into their performances. With a gymnastics background, Bonaly incorporated difficult jumps and turns into her routines with ease. She struggled, however, to fit the ice princess aesthetic. Pair skater, figure skating choreographer, and television commentator Sandra Bezic once stated, “I’d like to see her stop jumping for six months and learn to skate.” She received 5.0s, 5.1s, and 5.2s in the artistry section. Although the point system then ranged from 0-6, low 5s were low marks. Skaters like Tonya Harding often faced similar criticisms for lack of artistry. But for Bonaly, it’s a little more layered.

Image: Radiolab

It Was Time To Readjust And Refocus

Bonaly received loaded comments from officials that some may agree alluded to her race. They’d comment on her exotic features, muscularity and she was once described as an unusual skater. As the only Black skater competing in these competitions, Bonaly knew all eyes would be on her all the time. In an interview with Radiolab she states, “well, you know, when you’re Black, you know, everybody knows that you have to do better than anybody else who’s white.” She never attributed her low scores to racism, she saw them as a sign to readjust and refocus. In 1992, she traveled to Southern California to train with highly respected American coach, Frank Carroll. His coaching allowed her to skate with more confidence and artistry; her scores reflected that. She placed second in the 1993 World Championships and placed fourth at the 1994 Winter Olympics. She set herself up to take home the gold at the upcoming 1994 World Championships.

Sometimes Trying Your Best Isn’t Enough

Bonaly skated a nearly perfect program and was well on her way to winning the gold. By the end of the competition, it came down to a tie between Bonaly and Japan’s Yuko Sato. Sato skated with the grace the figure skating world calls for. Her program, however, did not include as many spins and jumps as Bonaly’s. After a vote amongst the nine judges, it came down to a 5-4 ruling in favor of Sato. A disappointed Bonaly refused to stand on the podium with the other finalists and rejected her silver medal. To many, she looked like a poor sport. But can you blame her for getting so upset? Imagine facing constant ridicule about your lack of grace and how muscular you are, traveling to the United States to change your skating style, only to come up as second best. How would you feel?

Amateur Figure Skating Regulations Could Not Confine Bonaly’s Talent

In the 1998 Winter Olympics, Bonaly competed with a torn Achilles’ tendon and other various injuries. She knew she wouldn’t be able to land her triple axels and split jumps; her injuries hindered her chance at a top placement. This pain plus her frustration with the figure skating world caused her to whip out her secret weapon: a single leg backflip on ice. This move, famously known now as The Bonaly, is illegal and landed her in 10th place. But Bonaly didn’t care. The night of the Olympics she told the Miami Herald, “I wanted to do something to please the crowd, not the judges…the judges are not pleased no matter what I do, and I know I couldn’t go forward anyway, because everybody was skating so good.”

Image: The Mercury News and The Washington Post

Bonaly retired from amateur skating in 1998 and turned pro. Professional skating didn’t confine her to any rules or regulations. She excited crowds during each performance while skating without limits. Bonaly left a long-standing mark on the art of figure skating. She defied all rules, expectations, and stereotypes. She didn’t need to fit the mold of an ice princess, she stood her ground as the Ice Queen.